News

【Shinjuku】 “Introduction to Disaster Volunteer Training” held in English and Burmese

March 27, 2013

On March 3rd, PBV held an event called “Introduction to Disaster Volunteer Training: Training for Foreigners Living/Working in the Shinjuku Area” in Totsuka, near where PBV’s Tokyo office is located. The course was taken by 12 participants from 6 countries, including Burma, many of whom live in the Totsuka area.

This training session was organized in cooperation with the NPO Japan Association for Refugees (JAR). Both of our organizations have offices in Shinjuku and have been active in providing disaster relief to the Tohoku disaster areas.

Another unique trait that PBV and JAR share is that both organizations have involved many non-Japanese volunteers in our relief activities.

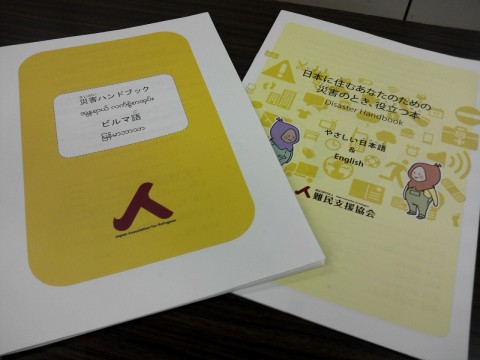

JAR has created its own “Disaster Handbook,” outlining what to do in the aftermath of a disaster. The book has been translated in to Simple Japanese, English, Burmese, Turkish, and Amharic.

JAR’s main focus is providing support for refugees who are residing in Japan.

When the earthquake and tsunami occurred, they immediately went to work dispatching volunteers to Tohoku. In 2011 alone, they coordinated international volunteers (including 200 refugees) for over 2,800 work days around Rikuzentakata in Iwate prefecture.

The JAR bureau chief, Ms. Ishikawa, gave a brief history of the organisation and introduced their activities.

As previously mentioned, PBV has sent groups of English speakers and Japanese/English bilingual volunteers to help with the relief effort in Onagawacho, Ishinomaki city in Miyagi prefecture.

So far, we have dispatched international volunteers from 56 countries around the world, totaling over 3,500 work days.

This training session also included several of our past international volunteers.

For foreigners who can’t easily read or write Japanese, the lack of information in the event of an emergency makes them disadvantaged during disasters. Foreigners comprise approximately 10% of the population in Shinjuku, and we wanted to change that way of thinking about them as people who are “disadvantaged” in a disaster, to “people who need support” in a disaster.

In that sense, they could be added to the same category as persons with disabilities, the elderly living alone, or infants and nursing mothers. Then, as “people who need support,” those 70,000 people would become part of the group that actually receives support.

*The above calculations are based on the number of registered residents; the current number of people who have applied as persons in need of support during a disaster is a little over 2,000 people.

Of course, there is still a lot of work to be done, but the experiences and successes of JAR and PBV prove that if we can just fill in the information gap caused by language differences, then it will be much easier to serve the foreigners who live and work in our community.

In other words, if we can only improve the methods of providing information in multiple languages, it will be possible to reduce the number of “disaster victims receiving support” and increase the number of “allies able to provide support.”

This photo shows several of our Burmese participants taking the training course with the help of simultaneous interpretation. Providing this kind of interpreting service and distributing emails and flyers in multiple languages is rather time-consuming at the start. But once you get used it, it is a relatively smooth process.

We also made some adjustments to the Japanese version of the training that is usually delivered.

For example, explaining that those in need of assistance should call “119″ for both emergency first aid and in the fire department; this may seem obvious to someone who has lived in Japan for a long time, but this may not be so well known among the foreign communities.

When cultural differences come into play, people may think about a subject differently even if the language of communication is the same. So we try to use photos to show the volunteers what kinds of tools they would need, and have the actual objects on display whenever possible.

In the workshop, we used a “Disaster Management Cycle” chart to illustrate what to do in the event of an earthquake in the city and how to be as prepared as possible.

This was the first time we held a class on disaster volunteering geared towards non-Japanese participants.

Many people had never heard about items like “disaster-prevention goods” and had no idea where to buy them. After the workshop, many told us that they had gained extremely useful information, and they would be sure to pick up some emergency-related gear in the near future.

Even better, several said that they would be interested in volunteering as well.

In Japan right now, the low birthrate and aging population is leading to an ever-decreasing number of youngsters. Even if we try to involve young people and engage them in volunteerism, as we did after the Hanshin and Tohoku earthquakes, this will not suffice in the event of a major disaster.

Disaster volunteerism will always play an important role after any disaster. However, we must also be able to mobilize enough people.

We believe this is the perfect time to expand the disaster volunteerism framework to include volunteers from all countries, regardless of their mother tongue.